DOMINICAN REPUBLIC

I Am; I Am Not

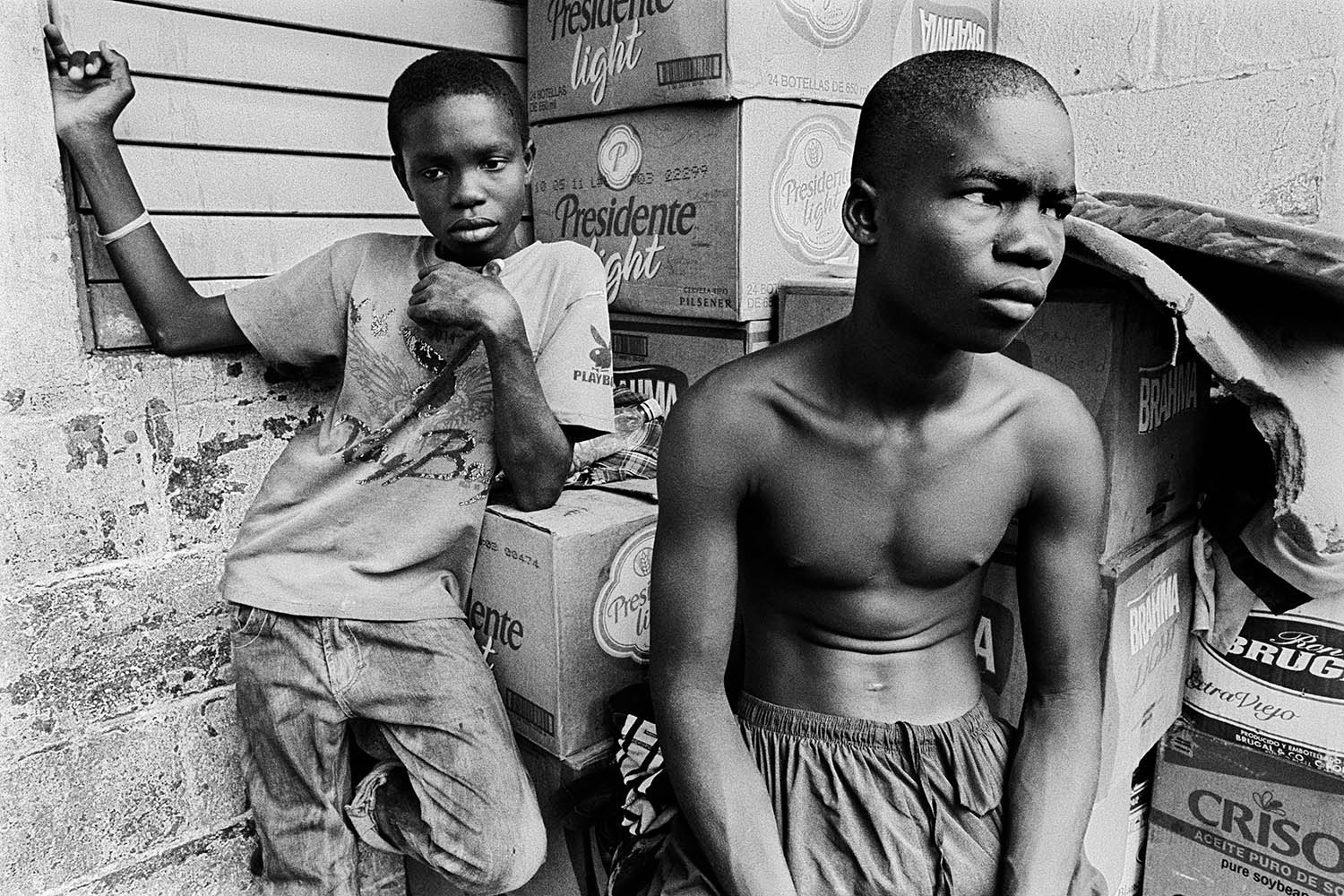

“I am here, and I am not here,” twenty-two-year-old Isidro says, shrugging his shoulders. “I want to study and be someone in life. I want to have a career.” He sits on the front porch of his family home in southern Dominican Republic. His mother stands nearby. Isidro’s parents were born in Haiti, but have not set foot there in fifty years. The Dominican Republic is their home. All ten of their children, including Isidro, were born here, as well as several grandchildren. When Isidro turned eighteen, he entered the local office of the Junta Central Electoral to request a copy of his birth certificate. The copy was required to apply for a National ID card (or cedula) and to apply for university. His request was denied and all of his documents kept under investigation. Why? Because his parents were Haitian, and new laws defined him as a foreigner. He walked out of the office, numb. Four years later, he remains stateless, without valid documents, unable to go to school or seek legal employment. His options are limited to working odd jobs, off the books, making whatever money he can. “I’m Dominican. I don’t know Haiti. Now I just exist, but I am fighting,” he says. “When you have documents, things change. The dreams you have come alive. But when they deny you documents, it is like they have tossed you away. They destroy you. They bury you in this life.”

"This country was made by sugar and we are the ones who have always worked like animals to cut it. But to this country and the people that lead this country we don't exist anymore.

For much of the twentieth century, hundreds of thousands of ethnic Haitians have lived in the Dominican Republic, where they have played an integral part in the country’s development. Yet their lives have been haunted for almost a century by racism and discriminatory policies originating from the highest levels of the Dominican government.

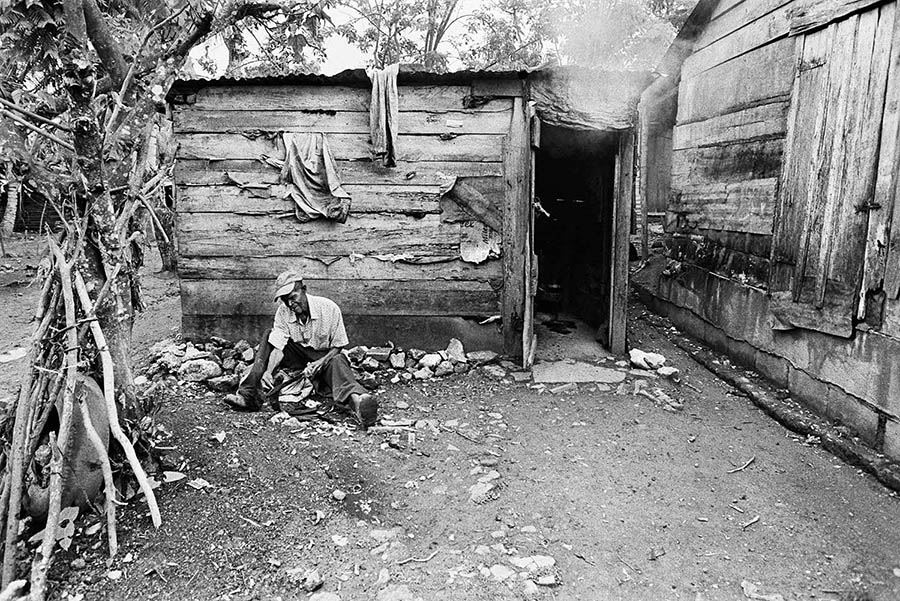

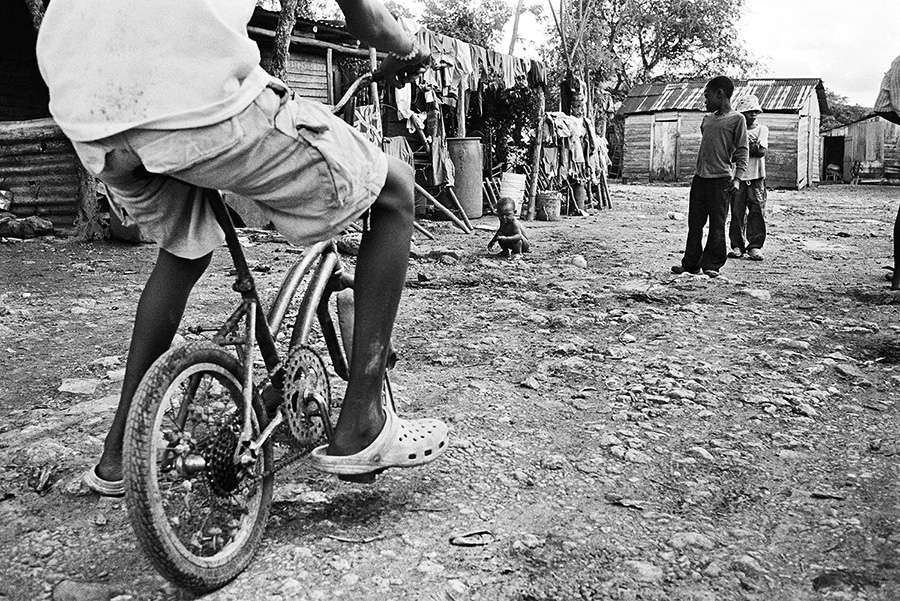

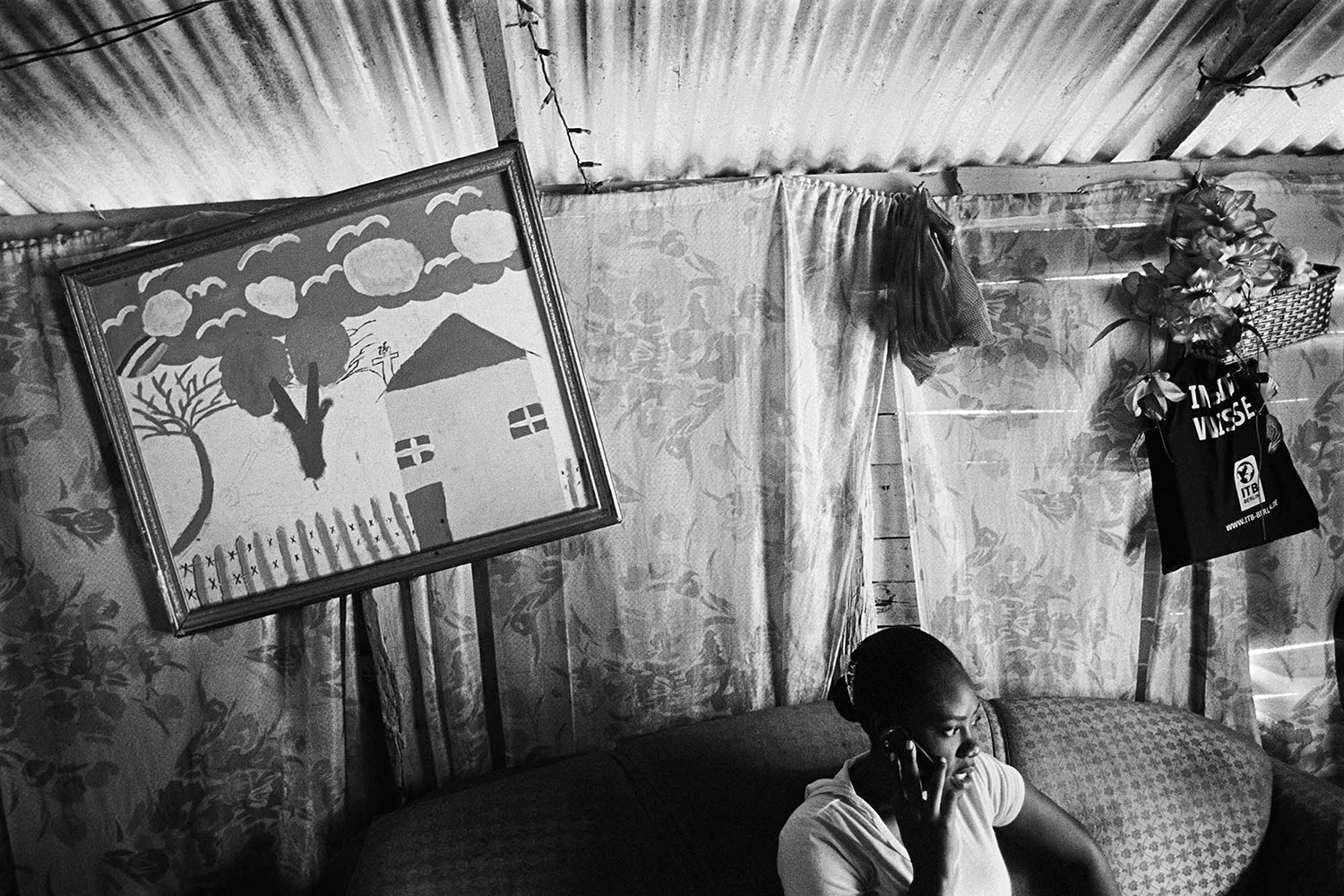

For decades, Haitians were brought to the country to work as cane cutters on sugarcane plantations. They lived in remote, slum-like bateyes and were issued a company ID, called a ficha. Dominican authorities accepted the ficha as a form of identification and for registering births. Over time, workers permanently settled in the country, started families and lost all ties to Haiti. As the sugar industry declined, many lost their jobs and have since been denied pensions. Their children were born on Dominican soil, grew up believing they were Dominican, worked as Dominicans in tourism or construction, only to have discrimination and politics strip them of their identity, rights and dreams.

"We keep working because we receive no pension. The old work until they die and the company provides a coffin."

For years, many children of Haitian descent born on Dominican soil often received Dominican citizenship. They received birth certificates, cedulas and passports and had access to schools, jobs and other social services. This started to change in 2004, when migration laws were amended to redefine Dominican nationality and exclude the Haitian community. The new migration law caused outrage and in 2005, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights found the actions of the Dominican government discriminatory and directed the government to change its policies. Claiming that issues of citizenship and nationality were the sovereign right of the state, the government rejected the legitimacy of the court’s decision.

Two years later, in 2007, registration officials throughout the country were ordered to withhold copies of birth certificates and identity documents from children of “foreign parents”—Haitians. Since then, thousands have been denied legal identities and the documents required to move forward with their educations and lives. A change to the Dominican constitution in 2010 was then followed by a landmark decision by the Dominican Constitutional Court in 2013, which retroactively stripped citizenship away from any person born to migrant parents in the country since 1929. The decision denationalized hundreds of thousands, and was yet another legal tactic by the government to systematically discriminate against Dominicans of Haitian descent and deprive them of rights, citizenship and their place in Dominican society.

“By saying we are Dominican we are not denying our descent. We are only proclaiming our rights…our right for a name and a nationality. It is the duty of the country to know and see us as Dominican without denying we are of Haitian descent.”

It is early morning in the batey Altagracia. One by one, children walk down dirt paths leading to an open space in front of the small community school. Several minutes later, the first teacher arrives, then another and another. The students take their book bags into school and then congregate again outside. They stand in orderly single-file rows according to age and grade. The morning sun shines in their faces. A young boy clips the Dominican national flag onto the rope of the flagpole. Slowly the flag begins to rise and the children recite the Dominican Pledge of Allegiance. They recite it in Spanish. They think in Spanish. Haitian Creole is a foreign language most do not understand. Just as the flag makes its final ascent to the top of the flagpole, the pledge is finished. A moment of silence follows. The younger students quickly file back into school, eager for classes to begin. The older ones in the eighth grade move slower. Most will never see ninth grade because they’ll need documents which can only be issued by visiting the local office of the Junta Central Electoral. Such a visit will have a predictable outcome. Like Isidro, they will discover themselves standing at the edge of a cliff, looking out at an empty future, denied a place in the country of their birth.