Bangladesh

THE FORGOTTEN

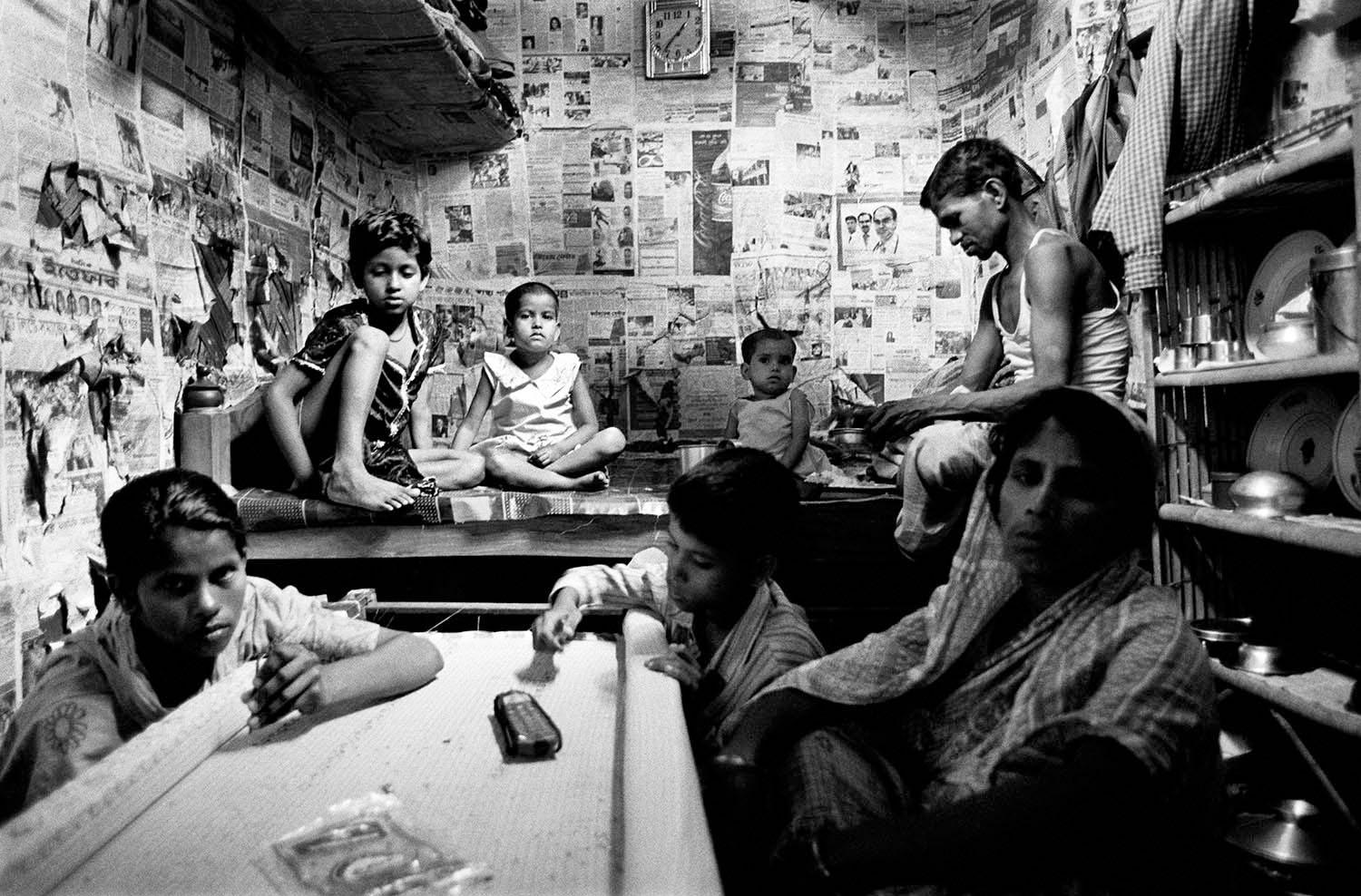

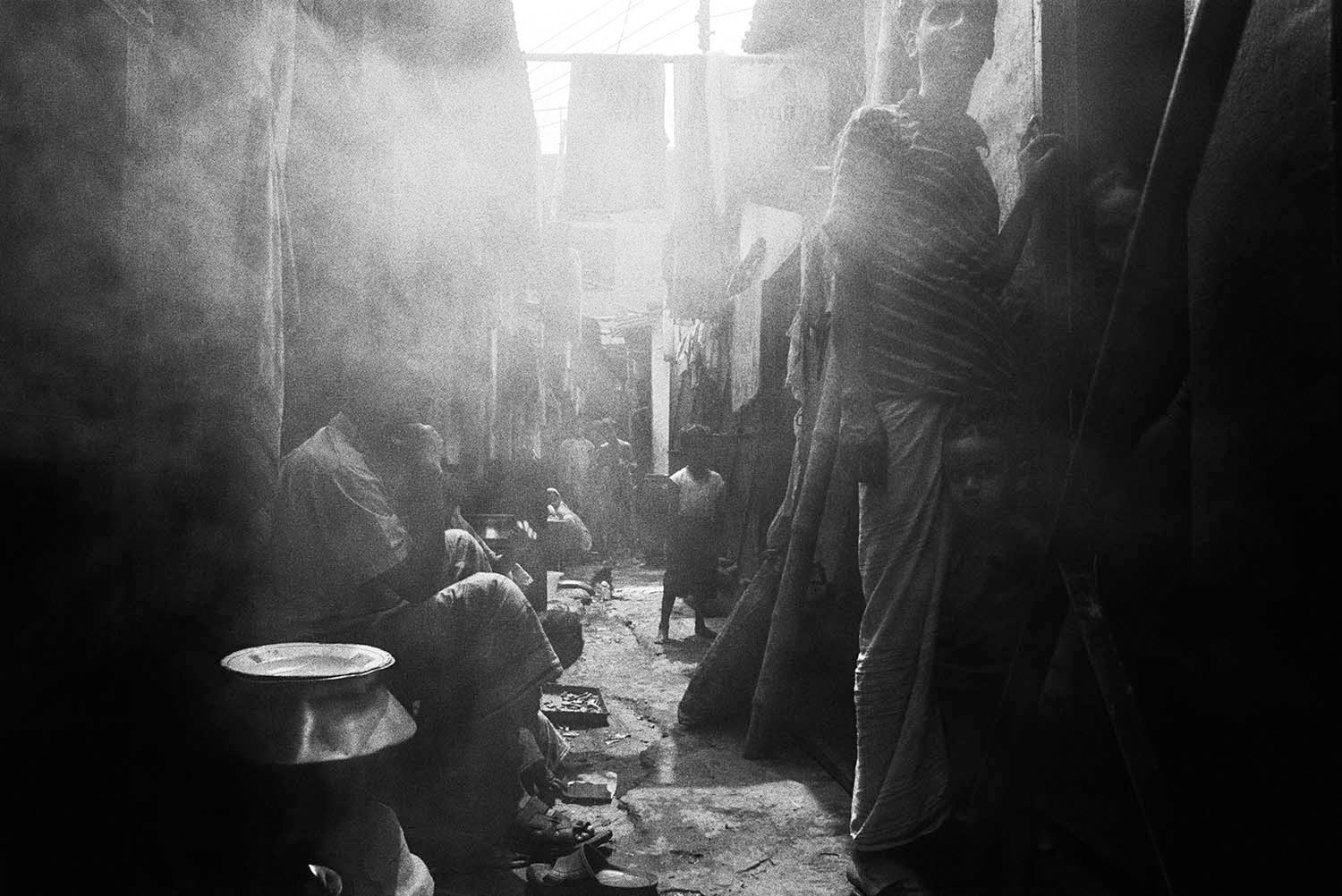

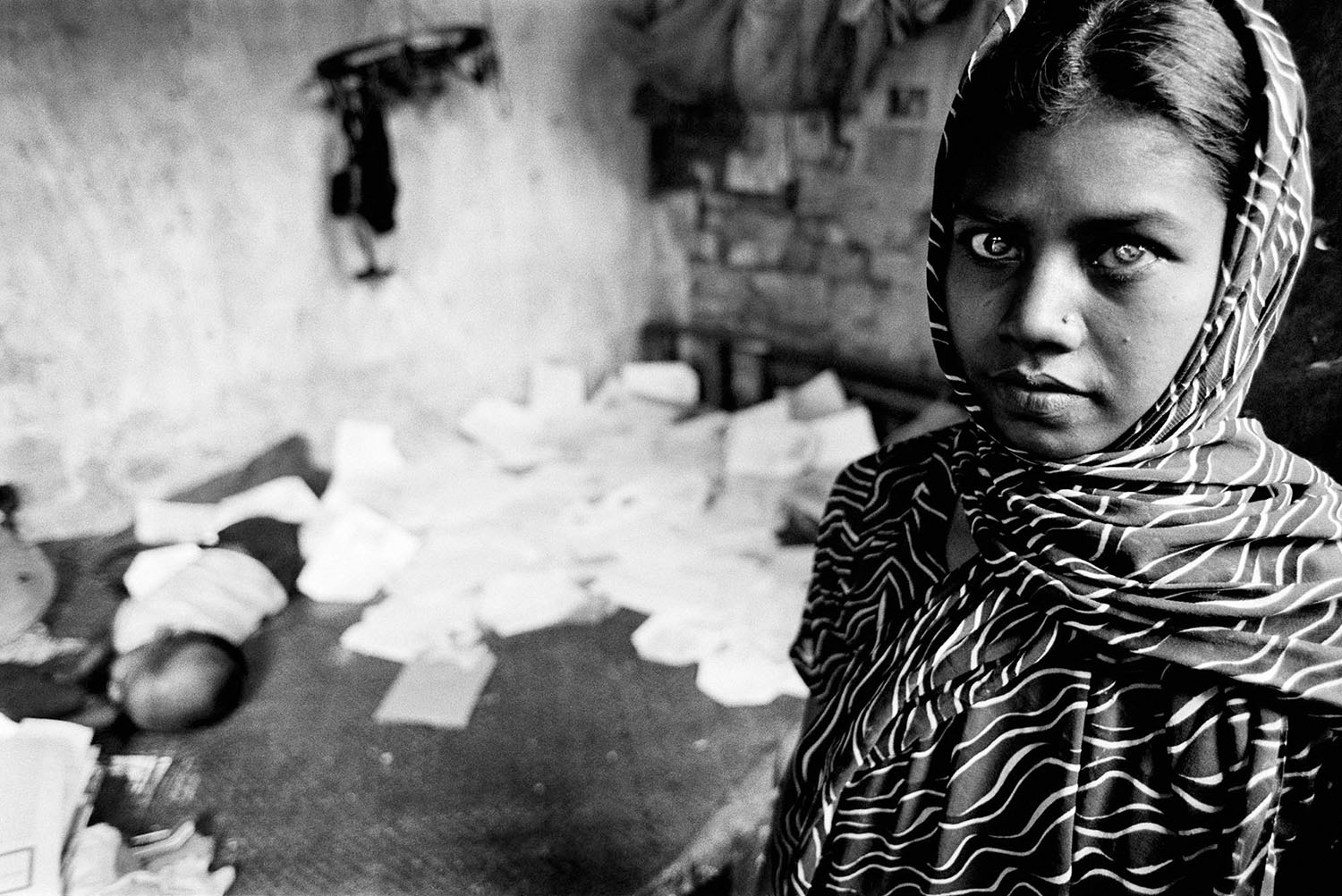

Down a dirty, bustling, chaotic side street in the Mirpur section of Dhaka, a maze of trash-ridden pathways wind through the cramped and crumbling structures of Kurmitola Camp. Streams of sewage flow between squalid brick-block shacks that are home to some four thousand people from the Urdu-speaking community commonly known as Bihari. Kurmitola was originally built as a camp of temporary shelters for displaced Urdu-speakers during Bangladesh’s war for liberation in 1971. From Dhaka to Rangpur, Jessore to Mymensingh, Khulna to Chittagong, there are over one hundred camps just like it, scattered in urban areas all over the country.

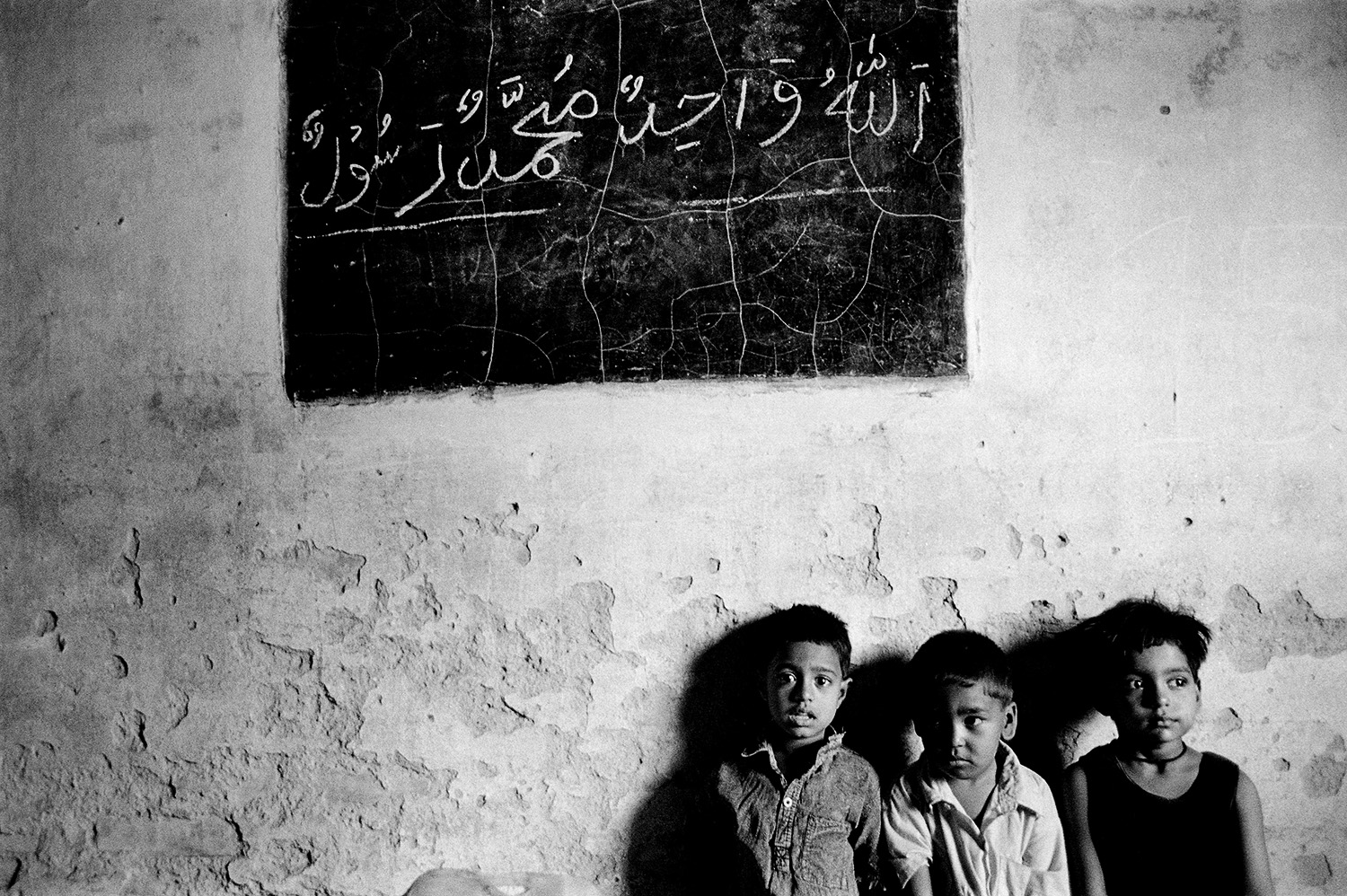

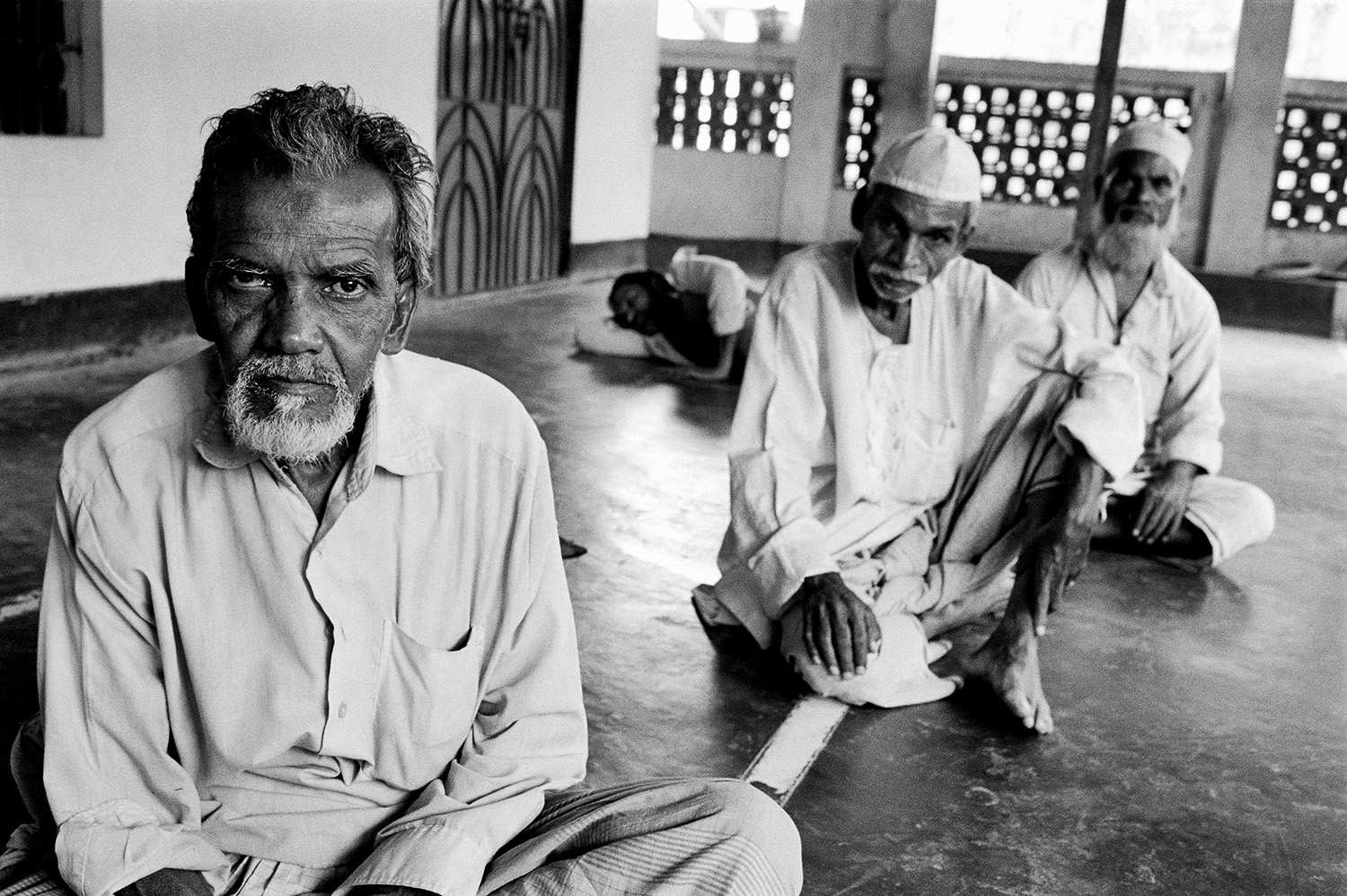

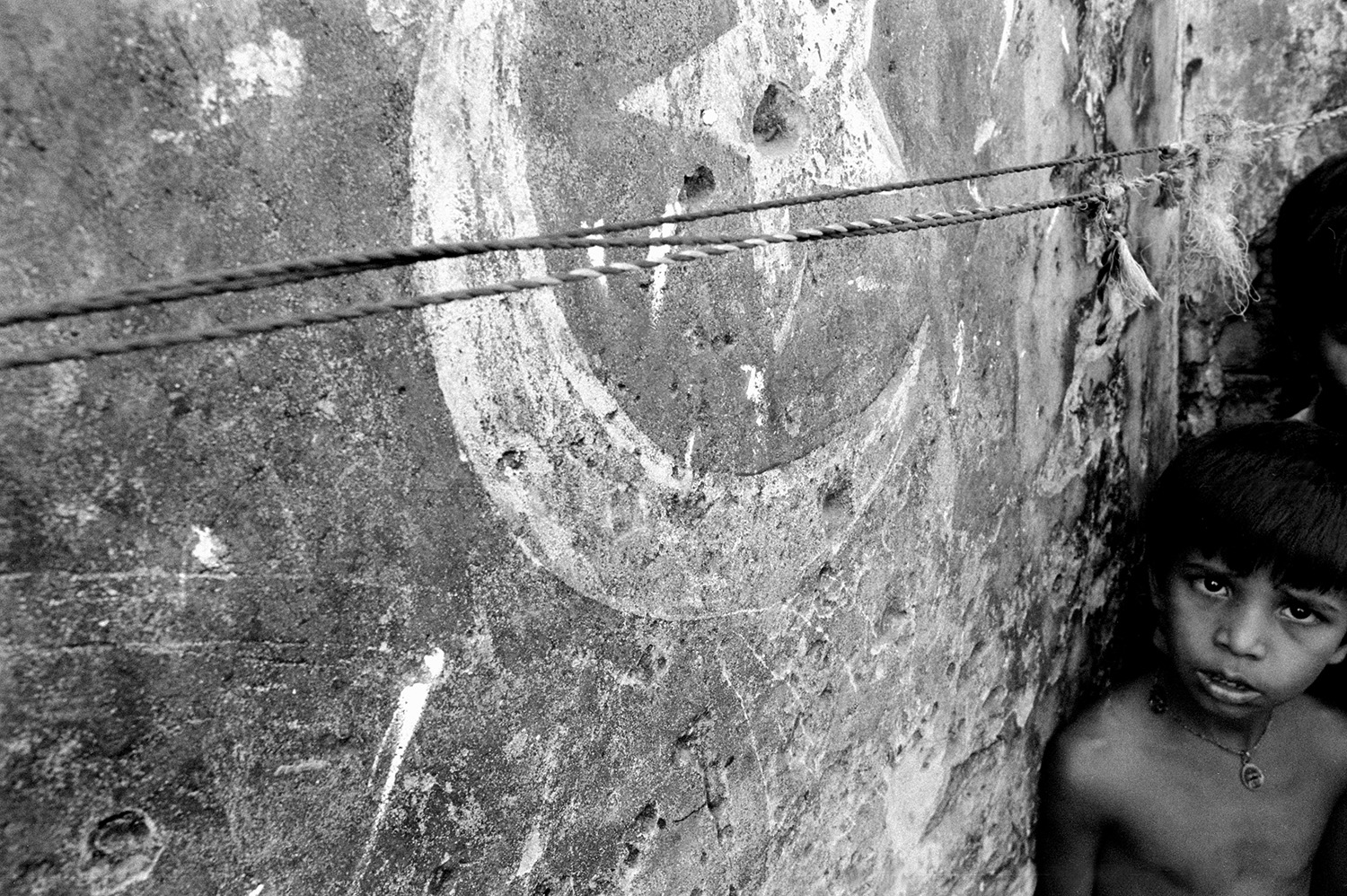

Hassan stands with several other young Bihari youths. All are in their late teens and early twenties. All work odd jobs as day laborers or as weavers sitting behind textile looms in tiny, humid handicraft factories in the camp. Life has stood still and the decay of time can be seen in every corner of the camp, as well as on the faces of most of the older residents. “Forty years of nothing,” said one older camp dweller. Education ground to a halt for Hassan and his friends when they finished the fifth grade. It is a dream that will never be fulfilled. They talk briefly about history, about the bitterness inside the older generation and the feeling of betrayal and loss that generation will always carry with them. Although they wake up each day denied their rightful place in the country of their birth, the younger Bihari do not let the bitterness of the older generation infect them.

“I speak Urdu, but I also speak Bengali. I was born as part of Bihari culture, but I was not born as someone from Pakistan. I was born in Bangladesh and I want to be a part of Bangladeshi culture too.”

In fear of communal violence following the partition of India in 1947, Indian Muslims fled into what became East Pakistan. Many were Urdu-speaking Muslims from the state of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. While both Urdu-speaking and Bengali Muslims originally considered themselves fellow-citizens of Pakistan, the two communities shared very little. The Urdu-speaking Bihari in East Pakistan spoke the same language and practiced similar cultural traditions as those of the ruling elite in West Pakistan’s capital of Karachi, giving them the opportunity to own land, work for the railroads, hold civil service positions and serve in the military. In the eyes of marginalized Bengalis, the Urdu-speaking Bihari were living in their newly-adopted home as a privileged class, with opportunities and social standing. By the late 1960s, the idea of a shared nation of Pakistan would come to an end.

"We have lived in these camps for many years. we have two rooms but they are very small, and we have seven people in our family. there is no space here for future generations."

When Bengali nationalists demanded independence from Pakistan in 1971, sparking the Bangladesh Liberation War, sectarian violence erupted between Bengalis and the Urdu-speaking community. Because of their historical allegiance to Pakistan, the Bihari were viewed as Pakistani collaborators, with enormous social, political and economic consequences. They were fired from their jobs, stripped of their land and assets and targeted in waves of violence. Hundreds of thousands were interned in camps built by the International Committee of the Red Cross throughout Bangladesh to shelter the displaced Biharis. After the creation of Bangladesh in 1971, nearly all cultural evidence of an Urdu-speaking community in Bangladesh was erased. The stateless Bihari were abandoned as citizens of a country a thousand miles away that no longer wanted them. Only a small portion of Bihari or “stranded Pakistanis” in Bangladesh were repatriated to Pakistan. In the land where they had been living for almost twenty-five years, they were unwelcome and excluded from citizenship by the new sovereign government.

"The older generation came from another part of the world. We were born here, but still we are suffering with the problem of identity."

Since 1971, some 300,000 Bihari have lived as ‘camp dwellers’, crammed into 116 overcrowded urban ghettos throughout Bangladesh. They lack basic services such as water and sanitation. Widespread discrimination and lack of citizenship and documentation have prohibited most Bihari from attending schools, obtaining legal employment, accessing healthcare or exercising any number of other civil rights. But a new generation of youth born in Bangladesh began to campaign boldly for equal rights. In 2001, ten youths filed a petition to the High Court demanding citizenship rights and in 2003, the High Court of Dhaka ruled in their favor. However, the judgment extended Bangladesh nationality only to the ten petitioners. In May 2008, another petition was filed and the High Court granted Bangladesh nationality and National ID cards to all Bihari born in Bangladesh after 1971. Yet, even with the landmark judgment, there has been little improvement in the lives of most Bihari. Several hundred thousand continue to live segregated lives in the same 116 squalid camps. Bihari in some instances continue to be refused passports and are denied employment in the government, civil service and armed forces. There is no special consideration given in educational institutions or in public sector employment for Urdu-speakers, as there is for other minority groups in Bangladesh. Still shouldering decades of stereotypes and social stigma, the community will take generations to overcome the consequences of having been stateless for decades.