UKraine

Lost Years a Stranger

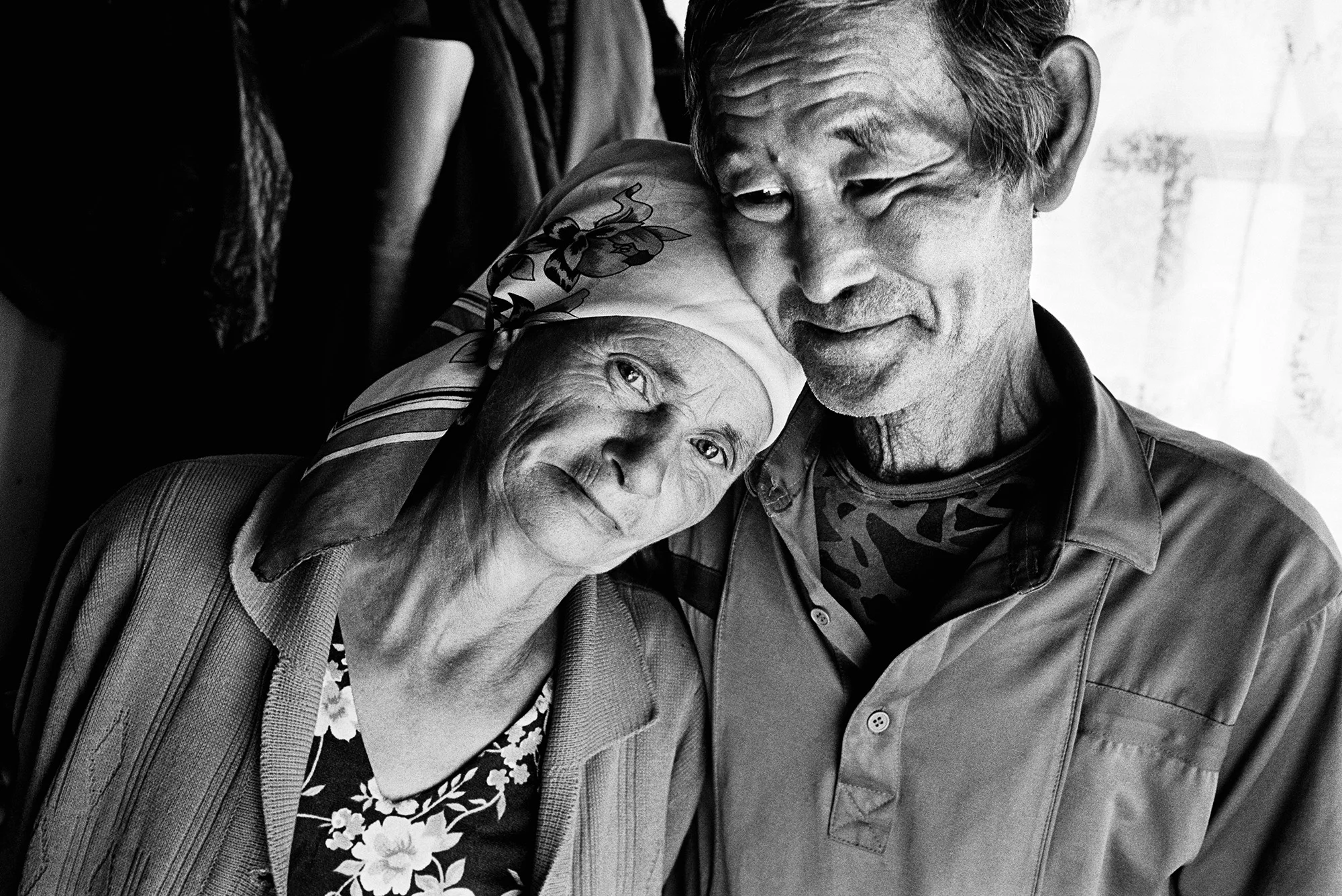

“I’ve come back to my motherland and people haven’t liked having us here,” 70-year-old Zarema says. “We asked for a plot of land but the village council said, ‘You don’t have citizenship, you don’t have passports, so we cannot arrange this land for you.’ People have made so many promises, but we still have nothing.”

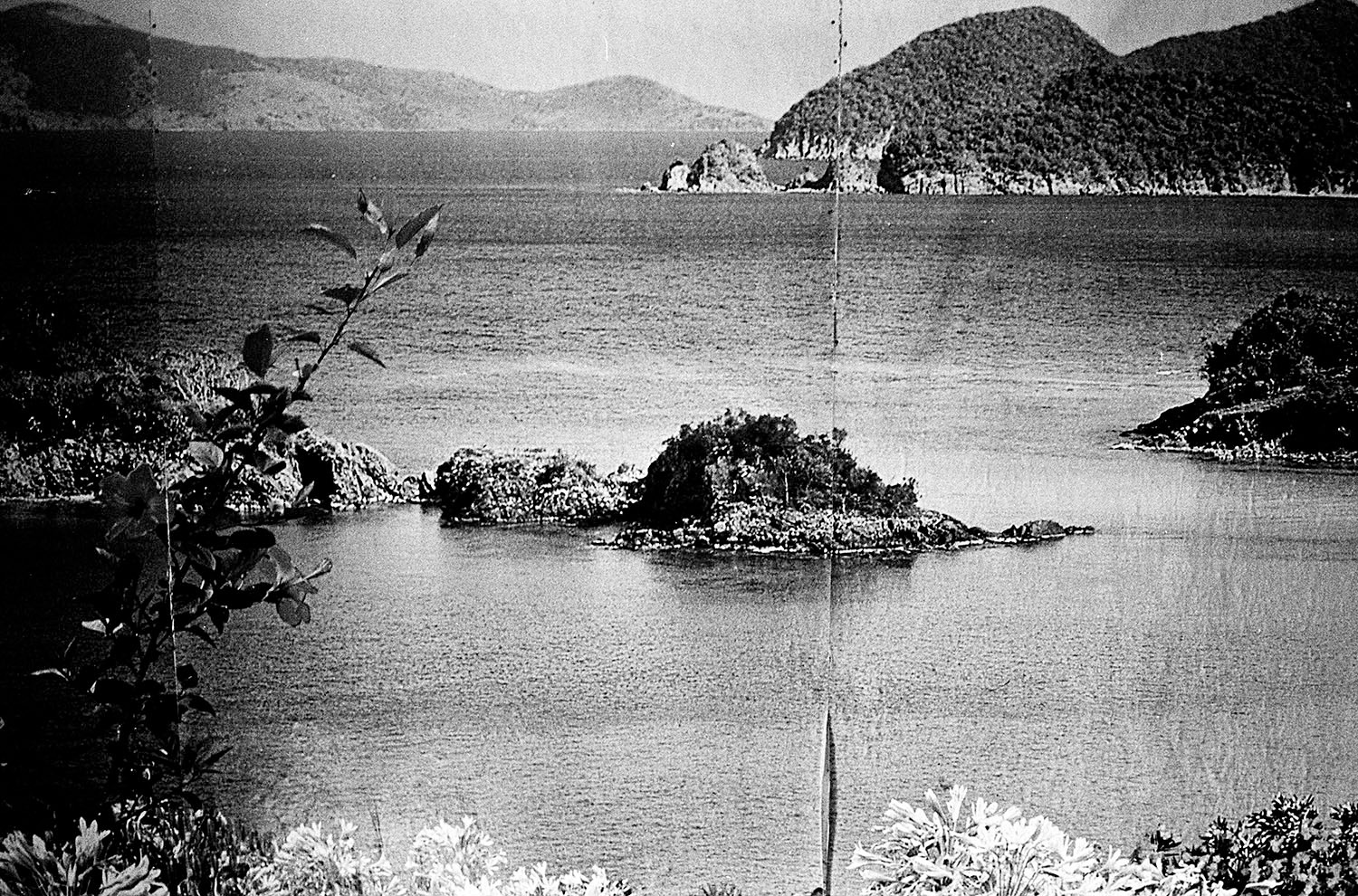

On May 18, 1944, Zarema was five years old. Her mother was away in a neighboring village. She and her brother and sister were staying with their aunt. Her father had been sent off to fight for the Soviet army in the war. He never returned. By 1944, Crimea had been liberated from the Germans, and the Crimean Tatars, a Muslim ethnic minority indigenous to Crimea, were falsely accused of collaborating with the Nazis. When Soviet troops burst into Zarema’s village that day, it felt like the world had been turned upside down. Together with the entire population of Crimean Tatars, they were loaded onto cattle trains and deported from Crimea to the human dumping grounds of Central Asia. Some two hundred fifty thousand people were deported; half would perish. One month later in Uzbekistan, she was reunited with her mother, who had fortunately survived the journey as well.

"After the deportations, we were lost...we've always felt like strangers. like we were foreigners in every country we went to."

Joseph Stalin’s deportations removed millions of people from their homelands. The purges also fortified popular suspicion and institutional discrimination toward ethnic minorities, a legacy that would live on much longer than the Soviet Union itself. Dozens of ethnic communities suffered a similar fate to the Crimean Tatars. In 1937, the entire ethnic-Korean population was deported from the Soviet Far East to Uzbekistan as well. Paranoid that the community would collaborate with the Japanese, Stalin decided simply to eradicate the community from Russia’s Far East border region. In the 1980s and 1990s, thousands migrated to Ukraine to work on farms. They would stay, make new homes, but also find themselves stateless.

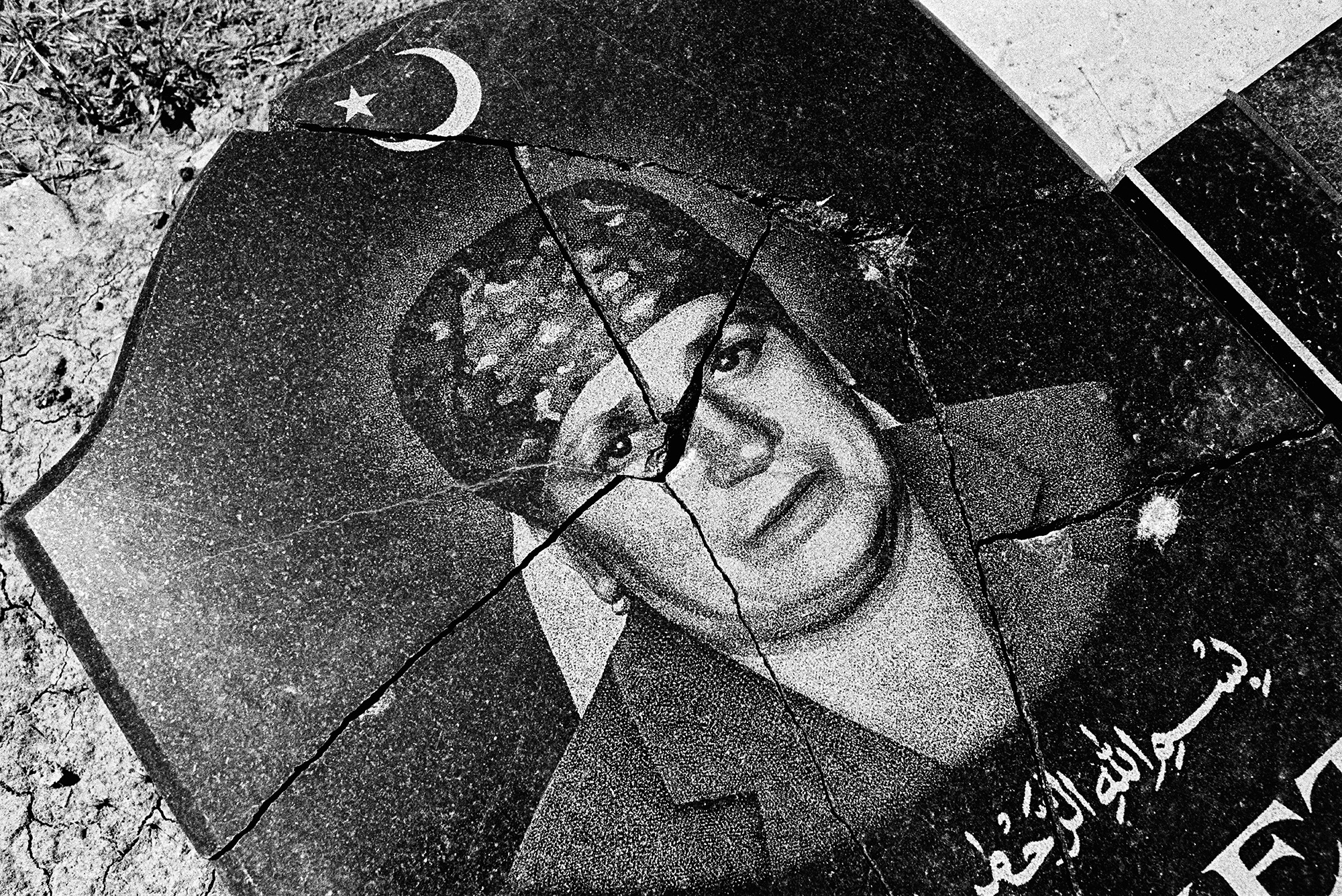

Back in Ukraine, Crimean Tatar businesses were abandoned and their property seized. The erasure of an entire community left an unnatural void in its wake, but ethnic Russians would soon move in and quickly make Crimea their own. A historical and political amnesia would settle over Crimea for decades. The Crimean Tatars would make a new life for themselves in Uzbekistan, uninvited in a new place, among a new community of fellow Soviet citizens who scorned them.

"when i was a boy in uzbekistan we would make bricks. we would turn to my father and say, 'why are we having to make bricks like this?' he would say, 'son, if we do this we can build a big house and we will sell the house and make a lot of money and we will use that money to move back and start a new life in the motherland."

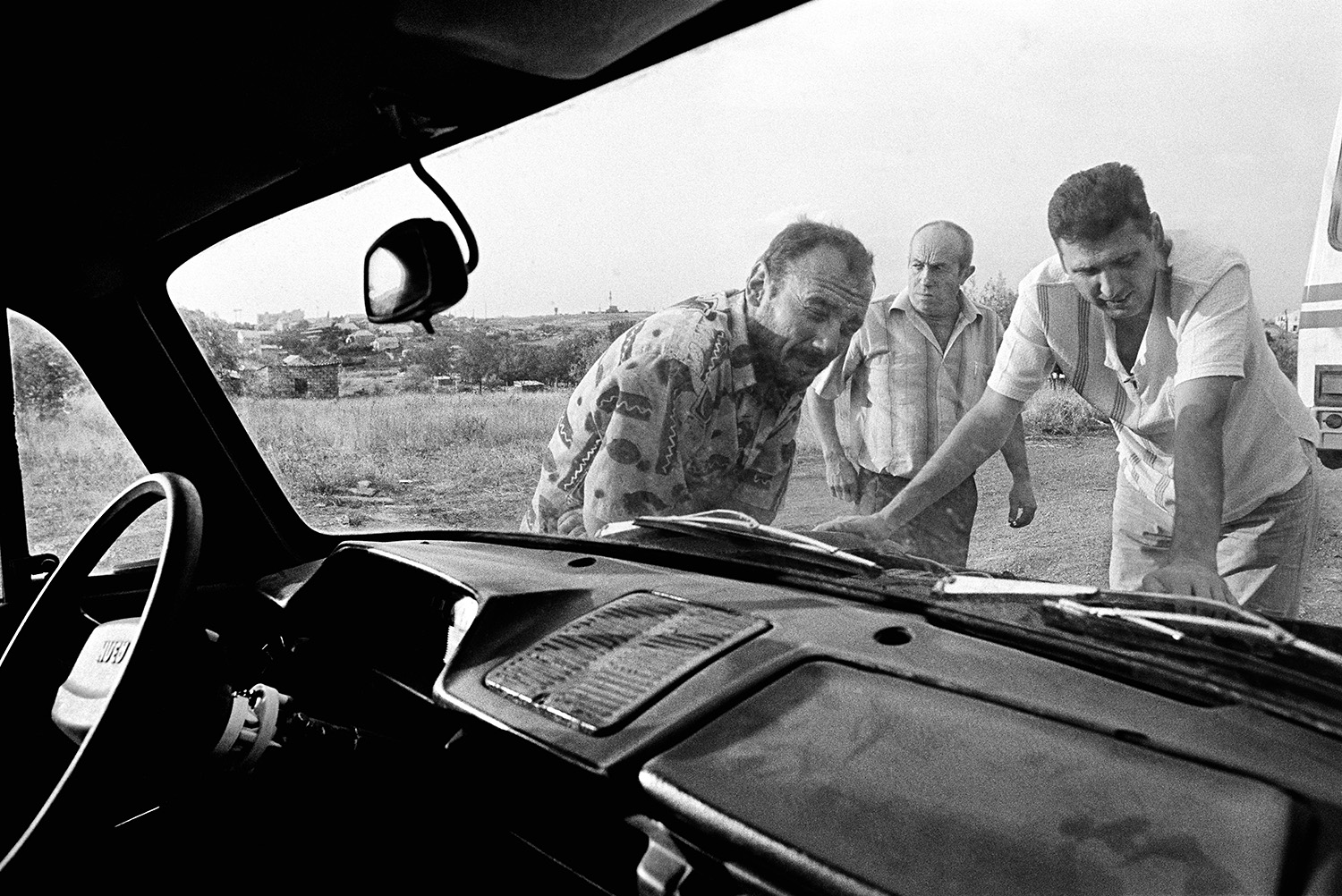

Almost fifty years would pass before Zarema and other formerly deported Crimean Tatars were permitted to return, but her exhilaration at setting foot back on Crimean soil was short-lived. The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 resulted in the creation of fifteen new countries. In the aftermath, hundreds of thousands of people from Latvia to Kazakhstan, and Estonia to Kyrgyzstan would find themselves unexpectedly stranded without citizenship in any of the new states that had replaced their former country. During the 1980s and 1990s, large numbers of Crimean Tatars were permitted to return to Crimea. Anyone legally residing in Ukraine at its declaration of independence in August 1991 was granted Ukrainian citizenship. Those arriving later, like Zarema, faced significant difficulties. Inconsistencies in legal and administrative procedures, debates over residency issues, discrimination and financial requirements prevented thousands from acquiring citizenship in either Ukraine or Uzbekistan. Two years after returning to Crimea, Zarema was neither a citizen of Russia, Uzbekistan or Ukraine. It would take Zarema and her family seven years to acquire Ukrainian citizenship and in that time, their lives were put on hold.

"I feel like nobody who belongs nowhere. like i don't exist."

hroughout the 1990s, several citizenship campaigns were launched and agreements made between Ukraine and Uzbekistan. Many returnees benefited from the programs but others were left carrying useless expired Soviet passports, unable to claim citizenship anywhere. Discrimination toward Crimean Tatars remains widespread today. With the annexation of Crimea by Russia in March 2014, Crimean Tatars have been viewed as antagonists to the occupation. The Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar people, the community leadership, is now in exile. Crimean Tatar TV has been shut down and Crimean Tatars are prohibited from celebrating cultural events openly, including the annual commemoration of the May 18, 1944 deportations. Members of the community have been pressured to renounce their Ukrainian citizenship and accept a Russian passport. Those who do not must register as foreigners on Russian territory and then live at the mercy of Russian immigration policies and restrictions. Those who remain are staying out of solidarity to their Crimean homeland, but many now experience difficulties acquiring valid documents like passports and National IDs.

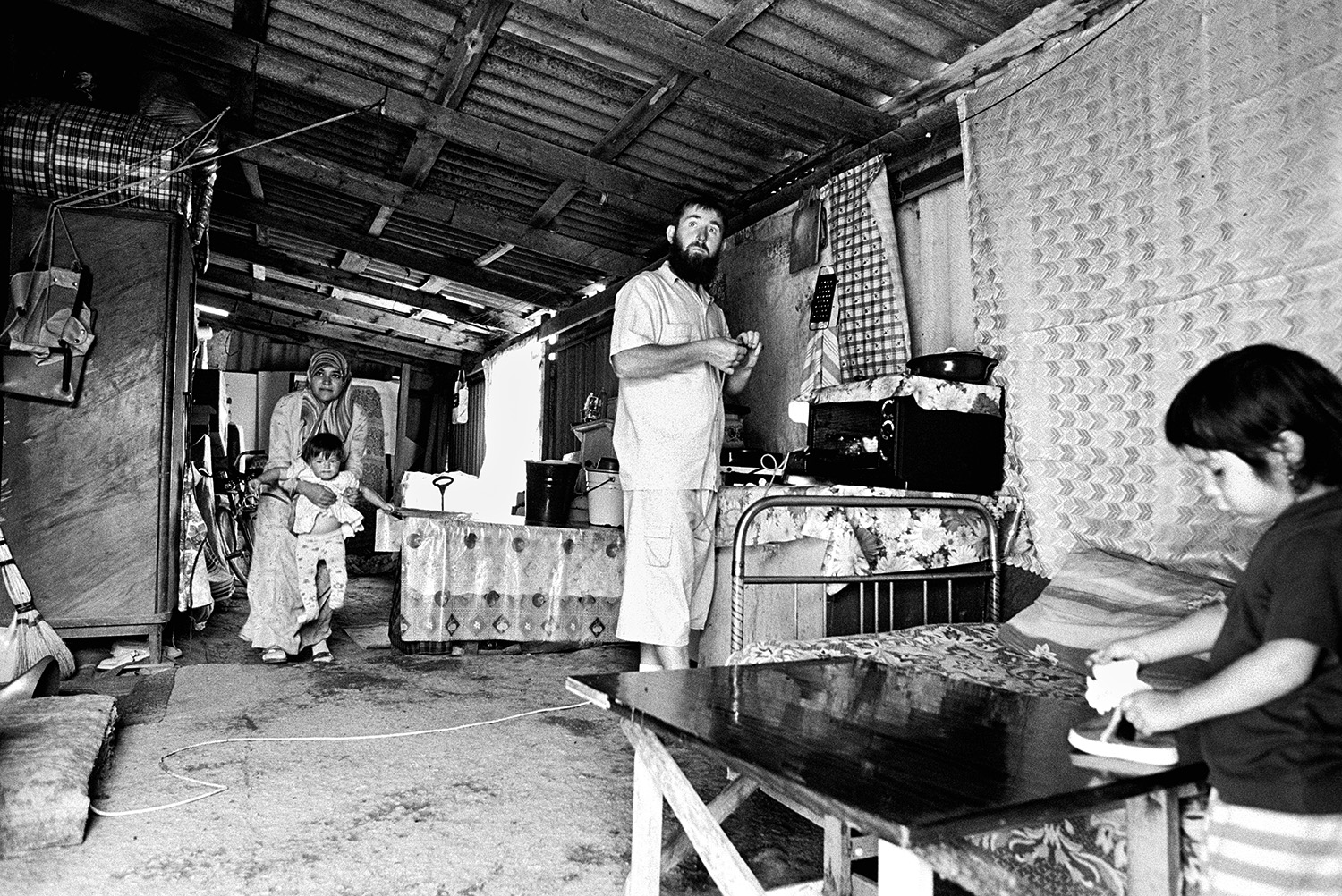

For Zarema and her family, the repercussions of statelessness shaped their lives for years. Having lost out on land allocation, they were forced to live in a two-room shack on someone else’s land. Unable to finish school and receive his diploma, her son found it almost impossible to obtain meaningful employment. For Zarema, the deportation and the statelessness had left a wound that felt deeper at this point in her life. She had lived her life as a stranger. Even after having found her way back to Crimea, she was still a stranger. Every month, the sight of the postman delivering pension checks to her neighbors caused Zarema to cry. “These have been lost years of my life,” Zarema says.