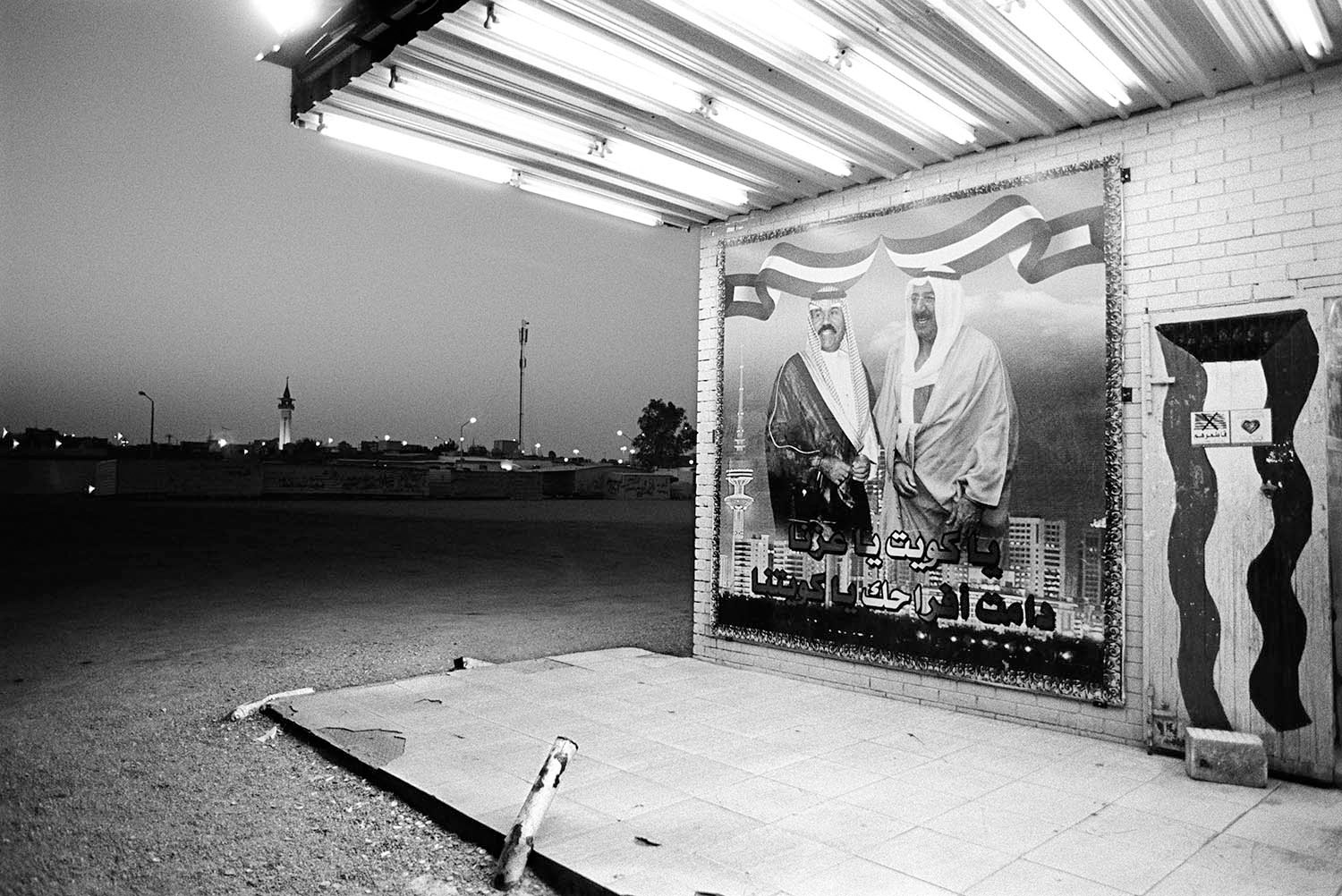

Kuwait

WITHOUT YOU MY COUNTRY

Fifty-four-year-old Faraj traces his family history in Kuwait back one hundred years. He began his service in the Kuwait Air Force in 1977. Faraj worked his way up in rank and was highly decorated for his loyalty and duty to his country. A letter from his superior officer praises him for his service defending Kuwait when Iraq invaded in 1990. But in 1991, Faraj was terminated. The dismissal was devastating. “I felt shocked and was also disappointed and felt pain. I thought, ‘Why? What did I do wrong? What crime did I commit?’ I felt like one of the essential parts of my body had been amputated,” he says. That year, Faraj was just one of thousands of men from his community who were fired en masse.

Only a small section remains of the original sur or old wall in Kuwait City. Built in 1920, the wall was constructed to defend and protect the lives and interests of the residents of Kuwait, and also to delineate those considered true Kuwaiti from the more nomadic, non-Kuwaiti outside the wall. Over the twentieth century, Kuwait grew from a population of fifty thousand to several million. It also became one of the wealthiest countries in the world because of its oil exports. While Kuwait has expanded beyond the boundaries of the old sur, this small sliver of what remains sits as a reminder to all in the gulf state. The definitions of Kuwaiti identity erected when the wall was built continue to stand as the foundations of how Kuwaiti identity and citizenship are defined today. The only difference is that now, the protection of the vast interests of those with from those who are without is not achieved through mud, brick and stone but through laws and policy.

"In 1991, they told us that we did not have a valid identification card to access the oil fields. we never had these ids before the invasion. when we couldn't show these new IDs, they fired all of us."

When Kuwait became independent in 1961, one third of its population was granted nationality. Another third became naturalized as citizens. The rest, like Faraj, were considered Bidoon jinsiya—without nationality. The Bidoon, as they are known (in Arabic, it means without), have been stateless ever since.

In 1959, Kuwait’s Nationality Law extended nationality to those who could show their families had settled in Kuwait prior to 1920 and had lived permanently in the country until the enactment of the Law. At the time, most Bidoon were eligible for nationality, but for various reasons failed to complete the application process before Kuwait’s formal independence in 1961, and remained classified as Bidoon jinsiya. Still, the Bidoon enjoyed many of the same rights and access to social services as other Kuwaitis, such as free healthcare and education. Bidoon worked in the same government offices, wore the same police and military uniforms, carried the same Kuwait Oil Company access badges and were largely seen and treated as equals. But in the mid-1980s, the Kuwaiti government made several amendments to its laws, gradually stripping the Bidoon of their rights. Up until Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990 and the ensuing liberation of Kuwait, the Bidoon community manned eighty-five percent of Kuwait’s army, yet in 1991, nearly all were fired. In less than five years (1986-1991) the Bidoon had become jobless, rightless and reduced to the status of “illegal foreigners.”

“i believe and feel like a body without a spirit.”

For Kuwaitis, citizenship is not only about identity and access to rights. It is the gateway to a secure future and a share of the country’s vast wealth. Today, a huge disparity exists between Kuwaitis and over one hundred thousand stateless Bidoon who consider Kuwait their home. For Kuwaitis, the government provides sizable benefits, such as housing subsidies, free healthcare and education, assured employment and large financial allowances for getting married and having children. Bidoon cannot own land and property and live in slum-like settlements on the outskirts of urban areas. Since 1986, many Bidoon children have not received birth certificates. Bidoon can only attend private schools, which most families cannot afford. They are prohibited from owning businesses, and the government’s “Bidoon Committee” has restricted companies in Kuwait from hiring Bidoon. This has resulted in high levels of unemployment and often forces Bidoon to work irregular jobs in the informal sector. Many Bidoon youth remain single because they lack the money to get married or because without money, documents or rights, they feel their family would have no future.

With the Arab Spring, Bidoon youth became more vocal in their desire for equal rights and citizenship. In 2011 and 2012, they staged peaceful demonstrations only to be met with violent crackdowns by Kuwaiti security forces. Bidoon from the younger generation continue to demand their rights and to be identified as full citizens of Kuwait. The older generation still battles with the harsh reality of having had this fundamental element of their identity—being Kuwaiti—torn away from them.

"Citizenship means for the Bidoon that the whole world acknowledges I am a human being. I have rights. I am a human being. Not so much for rights that are material, but the right to exist. I exist. I exist has a human."

Faraj still carries his military ID in his wallet even though it is of no use to him. It states his nationality as Kuwaiti. "While growing up, I knew I was Kuwaiti,” Faraj continues. “I don’t know anyplace else. But I’ve been called Bidoon. I’ve been called undefined, and then I’ve been called illegal resident. I don’t know why. I don’t know what happened. I don't know why we are destined to live like this."